OPEN A SEARCH ENGINE and enter the terms “ellesmere manuscript chaucer.” When hyperlinks appear, click the one that leads to the Huntington Library’s digital collections. What is the object that appears on your screen? San Marino, Huntington Library, MSS El 26 C 9 is commonly known as the Ellesmere Chaucer; it contains an early, deluxe copy of The Canterbury Tales, composed by Geoffrey Chaucer between 1380 and 1400. The hard-copy volume was made sometime around 1400, but the precise details of its creation and creators are much debated.1 When and why was it made? Who were its copyists? Can one be identified with the historical scribe Adam Pinkhurst? If so, moving out from the particular book to Chaucer’s lifetime of work, does that mean that one of the contributors to this early, luxurious copy of The Canterbury Tales can be linked to the scribe mocked in the lyric poem “Adam Scriveyn,” which has been attributed to Chaucer by the fifteenth-century scribe John Shirley? All of these questions coalesce around the object illuminated on your screen. But the much-studied object of scholarly devotion—the book written and decorated entirely by hand, in oak-gall ink, on processed animal skin—is patently not the same thing as the digitized object researchers and students access online, a point frequently made in publications on digitized books.2 When we work with a digitized manuscript, we work not with the manuscript itself but with digital images of medieval books, wrapped in layers of metadata, all of it mediated by unseen workers, using hardware and software most end users do not perceive, and served out to us through modern internet infrastructures and screens.

This book seeks to provide answers to the question, What is a digitized manuscript? While what we look at in a glow of pixels may appear to be a manuscript, made by medieval scribes and illuminators, touched and used by centuries of readers, it is not. So what is it that we work with when we use digital copies of rare books and manuscripts, maintained on distant servers and used by countless readers via thousands of glowing screens?

Over the past forty years, research in the humanities has been transformed by the digitization of a wide array of cultural heritage objects—including pre- and nonprint medieval texts.3 As this transformation has occurred, a consensus has emerged concerning what digitized books are not—they are not perfect surrogates for or transparent windows to their analog originals. Less ink has been spilled and fewer pixels illuminated concerning what digital manuscripts are. While there is an exciting literature emerging on digital manuscripts, scholarly end users still generally know little about how digital manuscripts are made, their recent history, and how new digital copies fit into the much longer history of copying medieval books across media.4 My preferred term for these objects, “digital manuscript,” emphasizes what I take to be a key element of these new copies and their long media history—the human labor that is always involved in their creation, preservation, and transmission. The word “manuscript” comes from the Latin manū, from manus—“hand”—and scrīptus, from scrībere—“to write.”5 The German term Handschrift shares this etymology. In both languages, the terms foreground the realities of human labor: this thing, “manuscript” says, was created through the work of human hands. Like their analog progenitors, digital copies are created through intensely hands-on processes, but names like “digital surrogate,” “digital facsimile,” and “digital avatar” keep that hands-on labor out of sight and therefore, I fear, out of mind. In describing these objects as “digital manuscripts” I seek to emphasize how much hands-on human labor continues to be the story of medieval manuscripts, especially as they are copied into new media.

The academic disciplines of bibliography and codicology analyze books as material, cultural objects. In much the same way that every medieval manuscript is a unique object, every digitization is unique. Even manuscripts copied according to “mass digitization principles” are shaped by particular individuals, institutions, and funding agencies as well as the historical moment and technologies of their creation. As digital archives continue to proliferate, we need a rigorous codicology for digital manuscripts and books, distinct from their analog, hard-copy originals. At the heart of this expanded codicology rest the same questions that we have long asked of digitized books’ analog originals: Who made this book? when? where? for whom? using what tools? to what end?

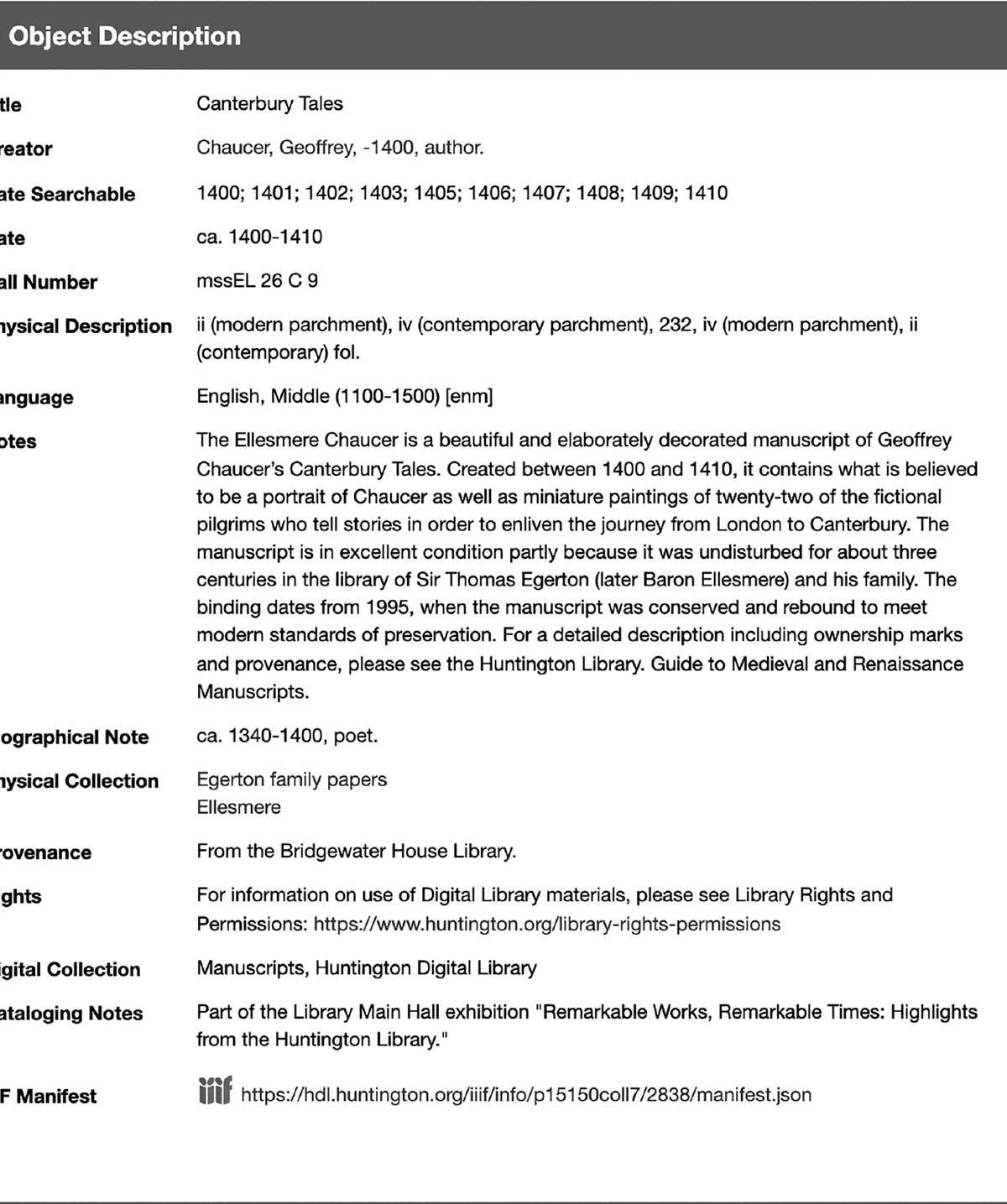

The rules of book history and manuscript studies do not end—or even change very radically—when a medieval book is copied into digital form. Our answers, however, grow more interesting and complex. Answering questions about when and why a digital book was made requires developing a curious double vision, simultaneously seeing the stages of medieval creation and digital re-creation—fostering an awareness of the ways digital resources are both true and untrue to their analog counterparts, both faithful and false witnesses. The digital copy of the Ellesmere Chaucer ca. 2017 exemplifies the benefits of employing this double vision. Below the larger digital photographs and smaller thumbnails that support easy browsing, an “Object Description” lists information about the object you see on your screen (fig. I.1).6

The title of the book is “Canterbury Tales” and its creator is listed as “Chaucer, Geoffrey,–1400, author.” Pinkhurst and the debates that swirl around him are nowhere to be seen. The object you see, the metadata say, is made up of two modern parchment flyleaves, one flyleaf of medieval parchment, 232 leaves of text and decoration, two more flyleaves of medieval parchment, and ends with four flyleaves of modern parchment. The notes also acknowledge that the six-hundred-year-old book’s binding is a recent addition, dating from 1995 “when the manuscript was conserved and rebound to meet modern standards of preservation.” That binding is absent in the digital copy (fig. I.2).

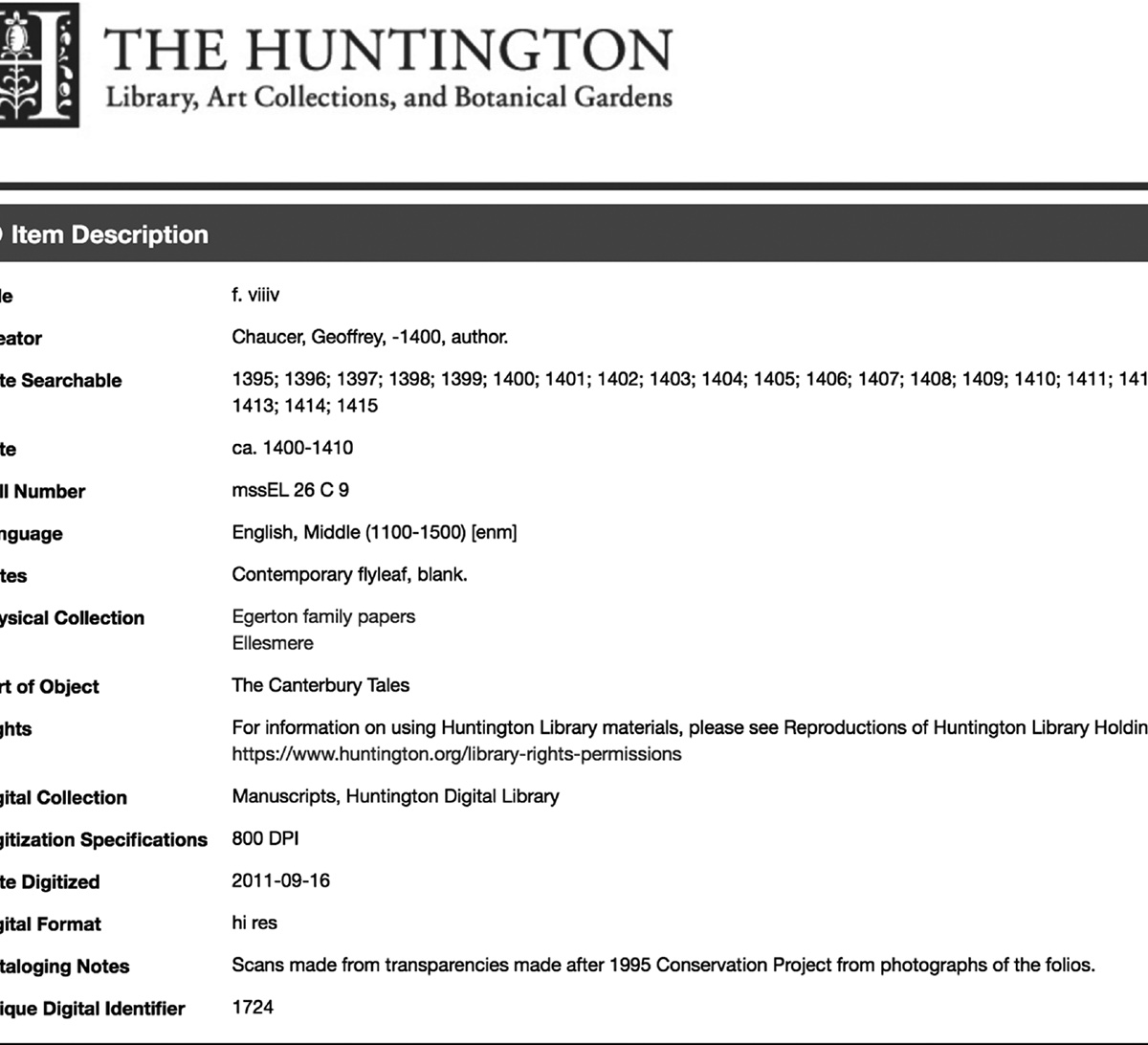

The digital manuscript loads already open to the first medieval parchment flyleaf, offering only a glimpse of something more modern on the far side of the gutter. Scholarship on digitized books conventionally warns us about this kind of absence, explaining that when bindings, flyleaves, book covers, and other content go unphotographed, each elision risks leading users astray. These gaps can be taken as evidence of digital distortion, used in cautionary tales exhorting researchers to never trust a digital copy to perfectly represent its hard-copy original. These warnings are useful in their way—but they still focus on what the digital manuscript is not, rather than what the digital manuscript is. In the case of the digital Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript, there are concrete, recoverable reasons why the binding is absent, and the key to that history lies in information that used to be visible in the Huntington’s descriptive metadata. Although much of the metadata in the “Item Description” section repeats information about the analog manuscript, a few elements preserve details about the origins of this digital copy, including “Digitization Specifications” and “Cataloging Notes” (fig. I.3).

Having access to this information about a digital manuscript empowers users to begin to answer the basic questions of codicology—about the digital copy as an object in its own right. The digital object on your screen was made, the metadata report, “from transparencies made after 1995 Conservation Project from photographs of the folios.” Knowing this and then connecting it to the hard copy’s conservation history clarify why the analog book’s modern binding is not included in the digital copy. In 1995, the Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript was disbound. It was photographed, still unbound, by Robert Schlosser, then principal photographer at the Huntington.7 After image capture, it received the new modern binding that is described in the digital manuscript’s metadata but not present in the digital manuscript. The 1995 binding and flyleaves are not in the digital image set, in short, because they did not exist when the digital manuscript’s source media were made.

Embedding the digital copy more firmly in the details of its production reveals how the copy of the Ellesmere Chaucer you see on your screen is the product of a particular moment in time and space. Scholarship on digital books has conventionally positioned “the physical” versus “the digital” as though technologically mediated, visual access to medieval manuscripts is a new thing. But the metadata for the digital copy reveal how much that binary oversimplifies the media histories of digitized books. Far from a Gutenberg parenthesis, skipping over five hundred years to directly connect the pre- and postprint eras, the digital copy of the Ellesmere Chaucer is deeply rooted in—is in fact inseparable from—an array of modern reprographic technologies, not the least of which is print.8 This knotted media heritage of one digital copy of a famous medieval English manuscript neatly exemplifies one of the credos of media archaeology: “Older technical media play an important part in the histories and genealogies, the archaeological layers conditioning our present.”9 The digital codicology I seek to promote builds on these insights from media archaeology. I attend to the histories and layers of media that separate original medieval objects from modern digital readers—because those layers condition all interactions with medieval books on screens. In extending the principles of codicology to include digital copies of medieval books, modern media history matters.

Developing a Codicology for Digitized Books

Codicology is the study of the physical makeup of codices, bound books.10 Unlike “philology” (which can mean studying the processes and tools of writing a text, but can also mean the love of words, learning, language, and literature; the academic discipline of studying language history; and a concrete set of techniques for making sense of texts), codicology focuses on the “objectness” of premodern books.11 That strict focus on materials and methods—the how, where, and why a thing is made, and who did that making—is precisely what I seek to extend to premodern books’ digital progeny.

Digitization is the “conversion of an analog signal or code into a digital signal or code.”12 The term “digitization” thus encompasses “image scanning, microfilming and then scanning the microfilm, photography followed by scanning of the photographic surrogates”—the method used to create the digitized Ellesmere Chaucer manuscript—“rekeying (typing in) of textual content, OCR (Optical Character Recognition) of scanned textual content, encoding textual content to create a marked-up digital resource, and advanced imaging techniques for large format or specialist items.”13 In this book, I focus on the digitization of medieval manuscripts—although my methods are extensible to other materials and media (see appendix). My case studies are manuscripts produced on either side of the English Channel in the mid-and later fifteenth century during the first fifty years of movable-type print in western Europe, handwritten books made during what has come to be known as the “incunabula period” of print. By virtue of what they are, as well as where and when they were created, these late medieval manuscripts deny tidy narratives of technological evolution and sudden replacement. These manuscripts’ modern digital counterparts, created between the 1970s and 2010s, similarly defy narratives of technological evolution that argue the rise of digital texts will bring about the death of analog books. Like media archaeology, to which it is indebted, digital codicology “deliberately resists an uncritically celebratory approach to technological narratives, just as it resists the curiosity-cabinet approach to treating the past as a collection of strange nostalgia objects.”14 Instead of treating digital manuscripts made in the 1990s as either lesser-evolved precursors to be discarded or dated curios to be recalled with amusement and pity, digital codicology studies them with the same rigor as it extends to digital manuscripts made in the 2020 s—to understand what digital manuscripts are, as well as the fears and expectations that swirl around them.

I focus, in particular, on two-dimensional digital images wrapped in layers of administrative, structural, and descriptive metadata—and not on methods such as OCR, multispectral imaging, or 3-D scanning—for two reasons. First, the world of cultural heritage is awash with two-dimensional digital images and their metadata. Given their abundance, we are profoundly in need of a language and methodology for analyzing them. My second reason for focusing on two-dimensional digitization is that these digital objects are not receiving the attention they deserve—in large part, I suspect, because they are so common. Writing in 1991, Eric Weiser rhapsodized about how successful technologies fade from view: “The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it.”15 This has been the case with digitized manuscripts. They have become so much a part of the fabric of everyday research, teaching, and outreach that they are transparent—as common and unseen as the air we breathe. Drawing inspiration from Daniel Wakelin’s work analyzing common medieval copying practices, I argue that an overemphasis on the quirky and exceptional rather than the quotidian and common has severely imbalanced critical conversations surrounding digitization and medieval books.16 The stories of remarkable manuscripts are frequently told. Extraordinary, new digitization methods will always draw attention. But the histories of more common digitizations—which comprise the majority of digital manuscripts available today—need to be uncovered and told with equal vigor. Moreover, if humanities researchers wish to be information-literate about our data, we have to understand how they come into being. And that means understanding the most common—and therefore most influential—processes of digitization.

1. Warner, “Scribes, Misattributed,” 55–100; Hanna, Introducing English Medieval Book History, 132–65; Roberts, “On Giving Scribe B a Name,” 247–70; Edwards, “Ellesmere Manuscript,” 59–73; Mooney, “Chaucer’s Scribe,” 97–138.

2. Edwards, “Back to the Real?” remains a key piece in these debates. See also Werner, Studying Early Printed Books, 139–40; Treharne, “Fleshing Out the Text,” 465–78; Nolan, “Medieval Habit, Modern Sensation,” 465–76; Echard, “Containing the Book,” 96–118, and her coda to Printing the Middle Ages.

3. There is a tenacious narrative about how the invention of print in the fifteenth century rapidly and totally replaced manuscripts. It is incorrect: manuscript culture persists for decades, even centuries, following the rise of the movable type printing press in western Europe—in the value still placed on handwritten texts over printed ones. Many of us still live, at least to some extent, in a manuscript culture, with handwritten signatures still acting as a stamp of authenticity beyond mere typed names. By saying “nonprint” instead of “postprint,” I also seek to hold space for that wider range of bookmaking cultures that did not find type a useful medium for their needs, and to acknowledge that print is neither the best nor only advanced book technology.

4. See, e.g., Warren, Holy Digital Grail; Medieval Manuscripts in the Digital Age, ed. Albritton, Henley, and Treharne; Endres, Digitizing Medieval Manuscripts; and van Lit, Among Digitized Manuscripts; Bamford and Francomano, “On Digital-Medieval Manuscript Culture,” 29–45; Mak, “Archaeology of a Digitization,” 1515–26.

5. Oxford English Dictionary (hereafter OED), s.v. “manuscript, adj. and n.”

6. These metadata are partially based on Dutschke, Guide to Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, 41–51, but are not an exact copy of that catalog’s contents. Vanessa Wilkie, interview with the author, October 22, 2021.

7. Woodward, “New Ellesmere Chaucer Facsimile,” 5–8.

8. Pettitt, “Media Dynamics,” 53–72.

9. Parikka, Geology of Media, 2–3.

10. Treharne, introduction to Medieval Manuscripts in the Digital Age, 6.

11. Orlemanski, “Philology and the Turn Away from the Linguistic Turn,” 158; Warren, “Philology in Ruins,” 60; Taylor, “Getting Technology,” 131–55; Turner, Philology, 386; and Wenzel, “Reflections on (New) Philology,” 12.

12. Lee, Digital Imaging, 3.

13. Terras, “Digitisation and Digital Resources,” 47–48; Deegan and Tanner, Digital Futures, 34.

14. Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, 56.

15. Weiser, “Computer for the 21st Century,” 94.

16. Wakelin, Scribal Correction, 13–14.